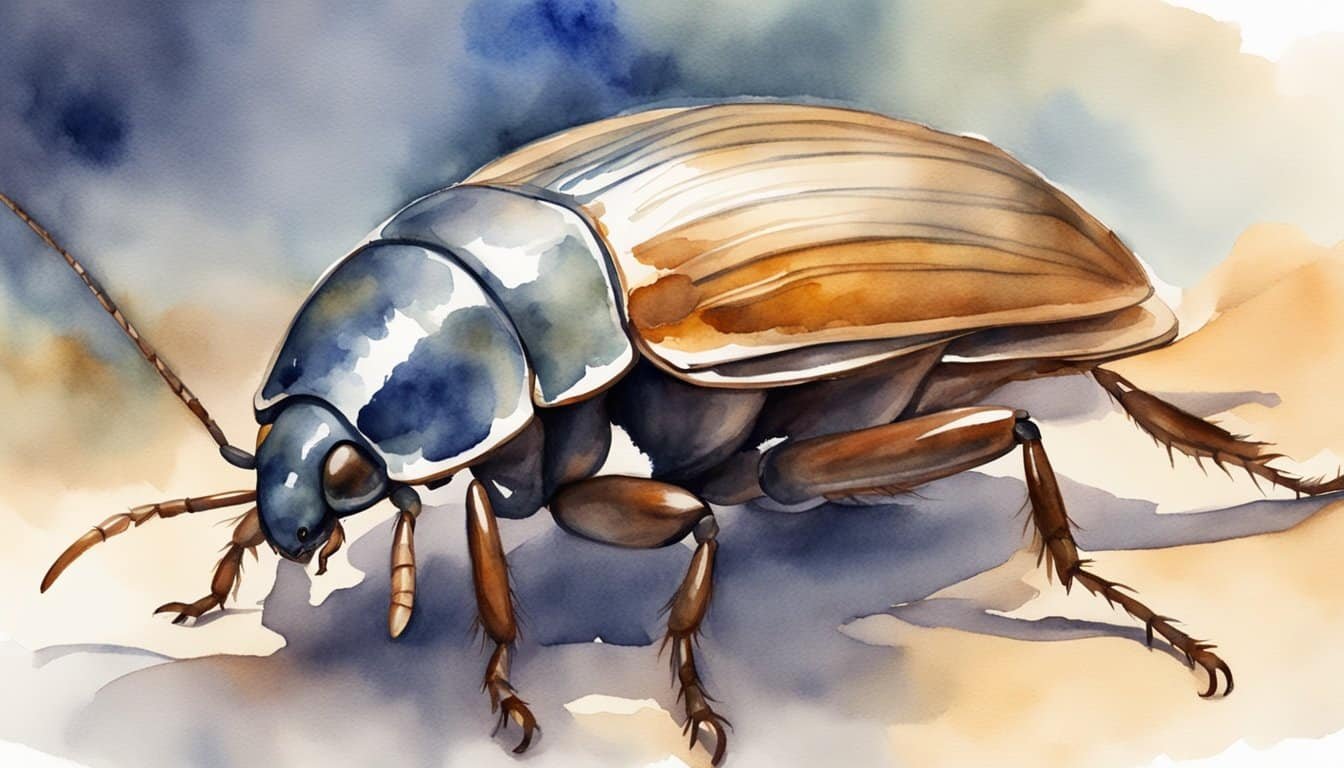

Cockroach Anatomy and Headless Survival

Cockroaches are equipped with an open circulatory system and a network of ganglia that allows them to endure even after losing their head. The absence of a head doesn’t immediately stop their bodily functions or lead to blood loss as it would in creatures with closed circulatory systems.

Bodily Functions Without a Head

Although a cockroach’s head houses its brain, they can survive without it thanks to the ganglia, clusters of nerve tissues, spread throughout their bodies. These ganglia control reflexes and local reactions, enabling a headless cockroach to still respond to its environment for a short period. The insect’s open circulatory system ensures that losing its head doesn’t cause a fatal loss of blood pressure, as their blood, or hemolymph, flows freely throughout their body cavity.

Headless Roach Lifecycle

When a cockroach loses its head, it’s not blood loss that ends its life, but rather dehydration. Without a head, a cockroach cannot drink water and eventually succumbs to desiccation. Their endurance is impressive; a headless roach can live for weeks, orchestrating movement through the still active nerve tissue in its body. Their longevity is facilitated by the insect’s slow metabolic rate and ability to regulate water loss, though they eventually cannot survive without taking in water.

Physiological Adaptations for Survival

Cockroaches are quite the survival artists, boasting physiological features that allow them to live for weeks without their heads. This can be attributed to their unique nutrient storage capacities and unconventional breathing mechanics.

Nutrient Storage and Usage

Cockroaches have a knack for storing nutrients which contributes to their infamous tenacity. As an arthropod, their bodies are adept at conserving energy, allowing them to survive for an extended period even when decapitated. They are cold-blooded, or more accurately, poikilothermic, meaning they do not require as much food as warm-blooded creatures since they do not need to maintain a constant internal temperature. This physiological trait ensures energy is used sparingly and efficiently.

- Energy Utilization: Minimal, due to poikilothermic nature

- Nutrition: Sufficiently stored to permit survival without immediate intake

- Hydration: Not as critical in immediate term due to slower metabolism

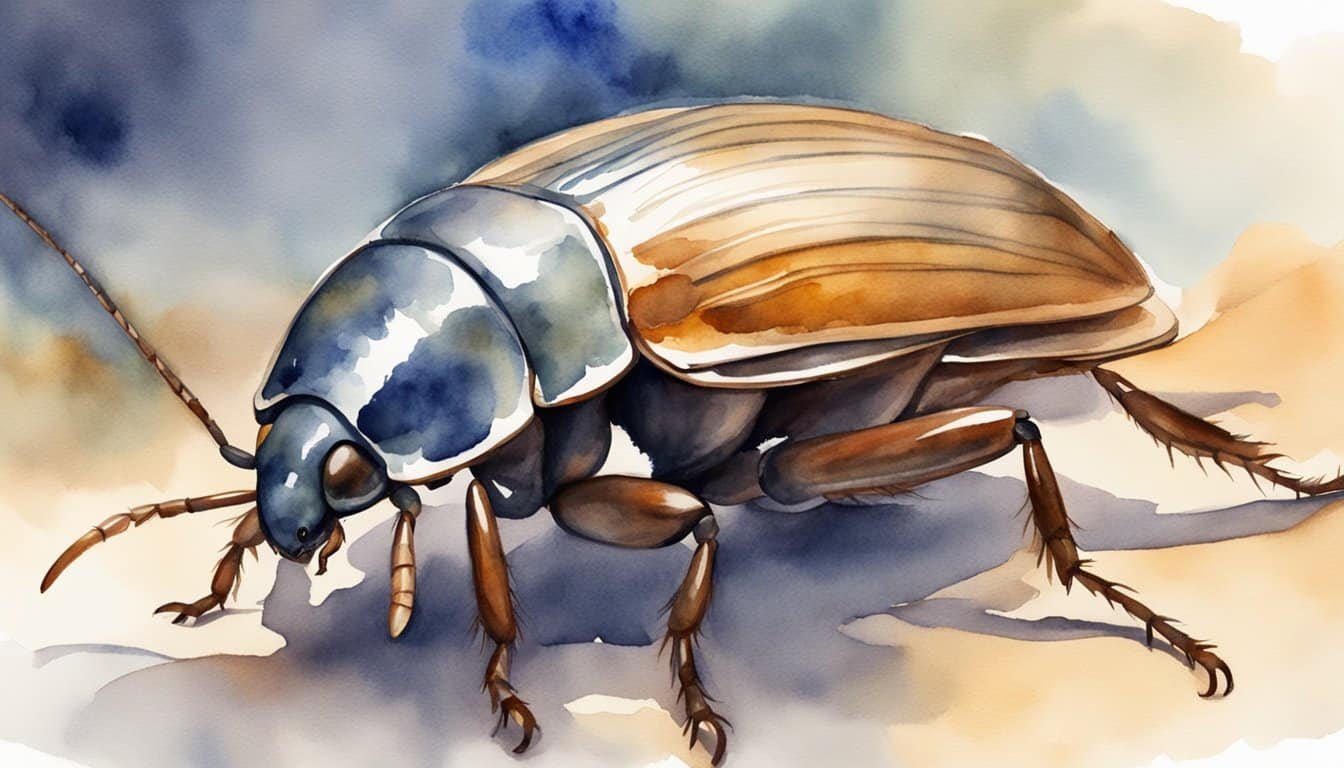

Respiratory Mechanics

Instead of relying on a head to breathe, cockroaches sport a series of small openings called spiracles along the sides of their body. These spiracles connect to a network of tubes known as the trachea, facilitating the direct flow of air to their tissues. This arrangement allows them to respirate without the need for a head or a brain to regulate breathing—another fascinating facet of their survival skills.

- Breathing: Direct air flow through spiracles and trachea

- Spiracles: 10 pairs along the abdomen, 2 pairs thorax

- Trachea: Extensive network for oxygen transportation

Through these extraordinary adaptations, cockroaches exemplify nature’s ingenuity at creating poikilothermic survivors with remarkable survival skills, even under the direst circumstances.

Cockroaches’ Interaction with Environment and Predators

Cockroaches are notorious survivors with some rather peculiar adaptations that allow them to thrive in various environments and evade predators. Their resilience includes the ability to live for a time without their head, which is both astonishing and a testament to their hardy nature.

Feeding and Drinking Behavior

When it comes to feeding, cockroaches aren’t picky eaters. They consume a variety of decaying organic matter, which often teems with bacteria and mold, becoming both a meal and a living environment for these insects. Astonishingly, cockroaches can also survive without food for a month, but their thirst for water is paramount—they’ll only last about a week without it. Their antennae play a crucial role in seeking out sustenance and sensing moisture in their surroundings.

Defensive Response and Threat Avoidance

Cockroaches have developed incredible defensive responses to fend off predators. With highly sensitive neurons in their antennae, they can detect the slightest air movements, possibly indicating an approaching threat. Upon decapitation, a cockroach can still react to its environment thanks to the clusters of nerve tissue within its body that act independently of the brain—a phenomenon that has piqued the interest of many an entomologist and neuroscientist. While they don’t bleed in the same way that vertebrates do due to a lack of pressure in their circulatory system, cockroaches that lose their heads can seal off the injury by clotting, enabling them to ward off viruses and other microscopic predators. This bizarre ability stems from their unique brain evolution and has become a curious subject for science journalism within the realm of entomology. Explore the studies that peer into the escape behavior and learning capacity of headless cockroaches, such as this fascinating account of cockroaches’ escape tactics and their ability to detect predators.