Origins of the First Americans

Unraveling the beginnings of the first Americans unfolds a story of human endurance and adaptability, as ancient peoples voyaged from Asia to the Americas. This journey, taking place tens of thousands of years ago, reveals a chapter in human history that has been pieced together through geology, archaeology, and genetics.

Beringia and the Land Bridge Theory

The theory of Beringia frames the narrative for the first migration into the Americas. During the Last Ice Age, sea levels dropped, revealing a stretch of land that connected present-day Siberia with Alaska. This area, known as the Bering Land Bridge, provided a vital passage for people moving into North America. Massive ice sheets would have impeded the way southward, making the timing of this journey critical.

New Discoveries and the Pre-Clovis Debate

New archaeological findings challenge the longstanding Clovis-first model, which posits that the first inhabitants of the Americas arrived approximately 13,500 years ago. Excavations at sites like Monte Verde in Chile present evidence of human presence that predates the Clovis culture. These discoveries have sparked the Pre-Clovis debate, suggesting that humans might have entered the Americas even earlier and through different routes, such as along the Pacific Coast.

DNA Evidence and Human Migration Patterns

Geneticists employ DNA sequence analysis to trace the ancestry and migration of the first Americans. Differences in DNA, particularly mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down maternally, reveal information about ancient populations. Genetic data indicates that early inhabitants had a unique genetic signature, pointing to isolation from other groups in Asia before their migration. The mutation rates in these genetic markers help scientists estimate the timing of these movements across the Bering Strait into the Western Hemisphere.

Through these subsections, the history and understanding of the first Americans, from their early origins in Asia to their eventual spread throughout the Americas, highlight an ongoing quest to unravel human prehistory. The land bridge theory, the emerging Pre-Clovis narrative, and complex genetic evidence converge to build a more nuanced story of these early adventurers.

Cultural and Environmental Adaptations

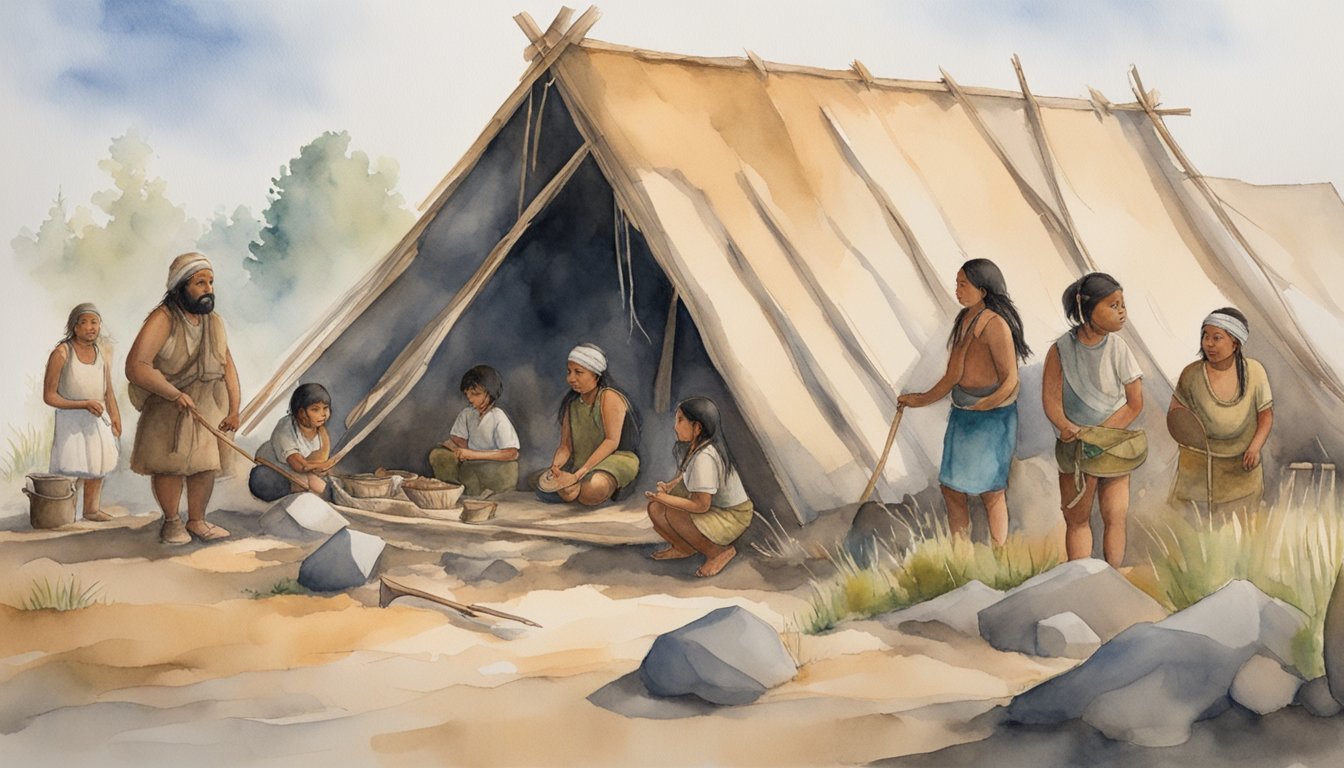

Adapting to their new environments, the first Americans developed diverse cultures and survival techniques. This section explores the innovations and strategies they employed to thrive in the prehistoric landscapes of the Americas.

Tools, Technology, and Survival

The first Americans crafted specialized tools, such as the iconic Clovis points, used for hunting large game such as mammoths. In areas like Monte Verde in southern Chile, evidence suggests the use of pre-Clovis tools indicating a sophistication in technology before the widespread adoption of Clovis culture.

Interaction with Megafauna and Flora

Humans engaged extensively with the megafauna, like the woolly mammoth, relying on them for food and materials. Remains of mammoths in places like New Mexico indicate that early societies utilized not only large mammals but also gathered a variety of seeds and plants such as desert parsley, adapting diets according to regional availability.

Early American Societies and Descendants

Early societies varied from hunters and gatherers in the Arctic regions to sophisticated fishers along the Baja California coast. These groups are the ancestors of modern Indigenous peoples of the Americas, as demonstrated by genetic studies and the discovery of skeletal remains like Kennewick Man and the Hoyo Negro girl, Naia. Their varied adaptations remain a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of early populations in the face of vast ecological challenges.