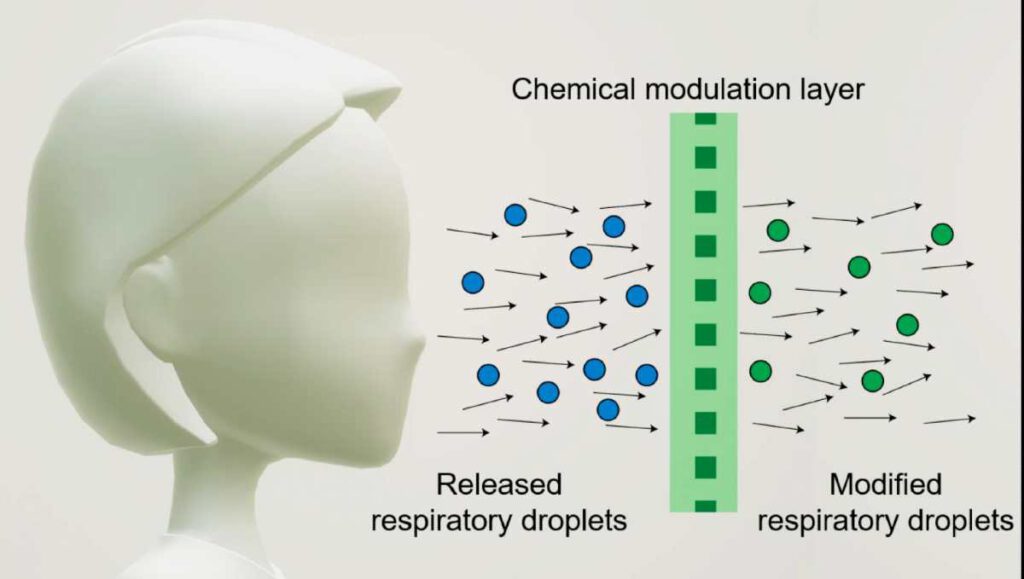

Researchers are designing a new kind of antiviral face mask with a special layer that sanitizes the mask wearer’s respiratory droplets, making the wearer less infectious to others.

The researchers, based at Northwestern University, published the results of their experimental design in 2020 in the journal Matter.

The central idea, which has received support from the National Science Foundation, is to modify mask fabrics with anti-viral chemicals that can sanitize the wearer’s exhaled respiratory droplets.

By simulating inhalation, exhalation, coughs, and sneezes in the laboratory, the researchers found that the typical fabrics already used in most masks work well for this new antiviral layer.

Such fabrics do not make breathing more difficult, and the on-mask chemicals do not detach during inhalation.

Antiviral face mask highlights the importance of protecting others

The spread of infectious respiratory diseases, such as influenza, SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, usually starts from virus-laden respiratory droplets.

Infected people exhale these droplets when they cough or sneeze.

Many of these droplets land on surfaces such as doorknobs, tabletops, handrails, and touchscreens, turning them into potentially infectious objects.

That’s why reducing the number of these exhaled particles helps to slow down the spread of the virus.

“Masks are perhaps the most important component of the personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to fight a pandemic,” said Northwestern’s Jiaxing Huang, who led the study.

His research explores “chemical modulation strategies” that kill the virus in the droplets as they pass through a mask.

“We quickly realized that a mask not only protects the person wearing it, but much more importantly, it protects others from being exposed to the droplets (and germs) released by the wearer,” he said.

Emphasizing this “social” dimension is an important part of changing the way people think about wearing masks.

This applies especially to people who feel there is no need for them to wear masks.

“Perhaps we should call it public health equipment instead of personal protective equipment,” Huang said.

The goal, and the results

Although today’s masks can block some exhaled respiratory droplets, many droplets (and their embedded viruses) still escape.

Huang’s team aims at chemically altering these escaped droplets to render the viruses inactive.

To accomplish this, Huang sought to design a mask fabric that met three criteria.

It had to allow for easy breathing, and be able to carry antiviral agents that readily dissolve in the escaped droplets.

Likewise, it could not contain chemicals or easily detachable materials that might be inhaled by the wearer.

Best chemical fit: phosphoric acid and copper salt

After performing multiple experiments, the team selected two well-known antiviral chemicals: phosphoric acid and copper salt.

These non-volatile chemicals were appealing for two reasons.

Firstly, neither can be vaporized, and thus potentially inhaled.

Secondly, both create a local chemical environment that is unfavorable for viruses.

“Virus structures are actually very delicate and brittle,” Huang said. “If any part of the virus malfunctions, then it loses the ability to infect.”

Huang’s team grew a layer of a conducting polymer polyaniline on the surface of the mask fabric.

The material adheres strongly to the fibers, acting as a reservoir for acid and copper salts.

The researchers found that even loose fabrics with low-fiber packing densities of about 11%, such as medical gauze, still altered 28% of exhaled respiratory droplets by volume.

For tighter fabrics, such as lint-free wipes (the type of fabrics typically used in the lab for cleaning), the layer modified 82% of respiratory droplets.

Huang hopes the current work provides a scientific foundation for other researchers to develop their own versions of this chemical modulation strategy.

Study: “On-Mask Chemical Modulation of Respiratory Droplets”

Authors: Haiyue Huang, Hun Park, Yihan Liu, Jiaxing Huang

Published: October 29, 2020

Photo: by Anna Shvets via Pexels